I think listening to U2 and the Beatles and trying to hear the differences is an excellent introduction to the next part of Hume's essay where he talks about the complexities of aesthetic judgment. Again, my comments follow in green.

The best kinds of music, as with all art, can be very subtle indeed and the right appreciation of them depends on learning to listen with attention and clarity. Any conclusion about the quality of a piece must follow an understanding of just what it is you are listening to. There may be things you need to know about how this kind of music tends to be put together (fugue, for example), or about the harmonic structures of the period. Then you need to be of a focused state of mind, without distractions. If only there were an easily accessible place on the web where one could find on-going suggestions of how to approach particular pieces of music... Oh, wait! Also, let me call attention to the brilliance of Hume's writing. He has to be read carefully, but what a wonderful prose stylist! I think he is also perhaps suggesting that listening to Bach on your iPod, while jostling along on a NY subway train may not be the best approach--that would constitute an "exterior hindrance"!But though all the general rules of art are founded only on experience and on the observation of the common sentiments of human nature, we must not imagine, that, on every occasion the feelings of men will be conformable to these rules. Those finer emotions of the mind are of a very tender and delicate nature, and require the concurrence of many favourable circumstances to make them play with facility and exactness, according to their general and established principles. The least exterior hindrance to such small springs, or the least internal disorder, disturbs their motion, and confounds the operation of the whole machine. When we would make an experiment of this nature, and would try the force of any beauty or deformity, we must choose with care a proper time and place, and bring the fancy to a suitable situation and disposition. A perfect serenity of mind, a recollection of thought, a due attention to the object; if any of these circumstances be wanting, our experiment will be fallacious, and we shall be unable to judge of the catholic and universal beauty. The relation, which nature has placed between the form and the sentiment will at least be more obscure; and it will require greater accuracy to trace and discern it. We shall be able to ascertain its influence not so much from the operation of each particular beauty, as from the durable admiration, which attends those works, that have survived all the caprices of mode and fashion, all the mistakes of ignorance and envy.

Here, I am gratified to point out, Hume is calling attention to what I have called the 'time quotient' of music (I even mentioned the example of Homer); the process by which, with the passage of time, the lesser pieces tend to fall by the wayside. How clearly and succinctly he explains phenomena such as Bach: at his death an obscure Saxon organist, but now, 250 years later, admired nearly everywhere. What Hume says about envy and jealousy is sadly true. Unless you are agent looking to make a buck off someone's career, it is not likely you are going to say anything nice about a performer, especially if they are represented by another agent. Singers are notorious for their hatred of other singers and few composers have anything nice to say about other composers. But fifty, a hundred years later, all that is left is the music. It is safe to say that the music of Bach has been beloved of more people every year since his death.The same HOMER, who pleased at ATHENS and ROME two thousand years ago, is still admired at PARIS and at LONDON. All the changes of climate, government, religion, and language, have not been able to obscure his glory. Authority or prejudice may give a temporary vogue to a bad poet or orator, but his reputation will never be durable or general. When his compositions are examined by posterity or by foreigners, the enchantment is dissipated, and his faults appear in their true colours. On the contrary, a real genius, the longer his works endure, and the more wide they are spread, the more sincere is the admiration which he meets with. Envy and jealousy have too much place in a narrow circle; and even familiar acquaintance with his person may diminish the applause due to his performances. But when these obstructions are removed, the beauties, which are naturally fitted to excite agreeable sentiments, immediately display their energy and while the world endures, they maintain their authority over the minds of men.

The color analogy is a pretty good one. Hume is making the point here that even though beauty is in the eye and ear of the beholder, still there is a kind of general similarity in the way these organs work. Colorblindness aside, if two people with normal vision are looking at the same color, they see the same color. To take a musical example, we can perhaps find an even better analogy. Take two people with normal functioning ears. With some ear training one might be able to identify intervals the other not. In other words, some people have a natural inclination to hear things musically, and others less so. With musical training you can hear the difference between a fourth and a fifth, easily know what meter the music is in (1234) and perhaps even write down the melody. All these skills certainly add to one's powers of discernment.It appears then, that, amidst all the variety and caprice of taste, there are certain general principles of approbation or blame, whose influence a careful eye may trace in all operations of the mind. Some particular forms or qualities, from the original structure of the internal fabric, are calculated to please, and others to displease; and if they fail of their effect in any particular instance, it is from some apparent defect or imperfection in the organ. A man in a fever would not insist on his palate as able to decide concerning flavours; nor would one, affected with the jaundice, pretend to give a verdict with regard to colours. In each creature, there is a sound and a defective state; and the former alone can be supposed to afford us a true standard of a taste and sentiment. If, in the sound state of the organ, there be an entire or considerable uniformity of sentiment among men, we may thence derive an idea of the perfect beauty; in like manner as the appearance of objects in daylight, to the eye of a man in health, is denominated their true and real colour, even while colour is allowed to be merely a phantasm of the senses.

I think I know what Hume is talking about here, but from many years teaching music students, I am tempted to put it differently. Isn't what he is talking about what we often call 'talent'? What is ordinarily called talent is usually the result of some natural inclination, many years of hard work and a bit of inspired guidance. Hume here is talking about the natural inclination part, I believe. The "defects in the internal organs" are what people call being tone-deaf. I have had adult beginners come to me and apologize for being 'tone-deaf' when they merely lack any training in how to hear. But some people do indeed have difficulty appreciating the pleasures of music due to a deficiency in listening. I'm not talking about anything physically wrong with the organs of hearing, just the brain's ability to sort out the data. What is it that I am hearing? I have a little anecdote to share: my first audition for music school was a very odd one. I had been in the music education program for a year, but for that, there was no audition. Music education majors do not receive private lessons on their instrument so they don't have to do the traditional audition which consists of going into a room with your instrument and performing in front of one or two professors of music. Egad! People prepare for that for years! I, having recently come from a rock background, had no idea of these things. In fact, the day I was supposed to do my audition because I was switching from music ed to being a real music major I didn't really know what was on the agenda and hadn't even brought my guitar. The music professor just gave me this frustrated look, dragged me into a practice room, played a low note on the piano said "sing it back", played a high note on the piano, said "sing it back", played an interval, major third or something, said "sing it back" and maybe played a minor chord and said "what kind of chord is this?" That was it. If I could do that, they could teach me the rest. Actually, I taught myself most of the rest. Still am. But you get my point? A professor of music can do a rough evaluation of your ability to learn music in about one minute with a piano. Or a zither, for that matter. You just have to know what to look for.Many and frequent are the defects in the internal organs, which prevent or weaken the influence of those general principles, on which depends our sentiment of beauty or deformity. Though some objects, by the structure of the mind, be naturally calculated to give pleasure, it is not to be expected, that in every individual the pleasure will be equally felt. Particular incidents and situations occur, which either throw a false light on the objects, or hinder the true from conveying to the imagination the proper sentiment and perception.

One obvious cause, why many feel not the proper sentiment of beauty, is the want of that delicacy of imagination, which is requisite to convey a sensibility of those finer emotions. This delicacy every one pretends to: Every one talks of it; and would reduce every kind of taste or sentiment to its standard. But as our intention in this essay is to mingle some light of the understanding with the feelings of sentiment, it will be proper to give a more accurate definition of delicacy, than has hitherto been attempted. And not to draw our philosophy from too profound a source, we shall have recourse to a noted story in DON QUIXOTE.

It is with good reason, says SANCHO to the squire with the great nose, that I pretend to have a judgment in wine: this is a quality hereditary in our family. Two of my kinsmen were once called to give their opinion of a hogshead, which was supposed to be excellent, being old and of a good vintage. One of them tastes it; considers it; and after mature reflection pronounces the wine to be good, were it not for a small taste of leather, which he perceived in it. The other, after using the same precautions, gives also his verdict in favour of the wine; but with the reserve of a taste of iron, which he could easily distinguish. You cannot imagine how much they were both ridiculed for their judgment. But who laughed in the end? On emptying the hogshead, there was found at the bottom, an old key with a leathern thong tied to it.

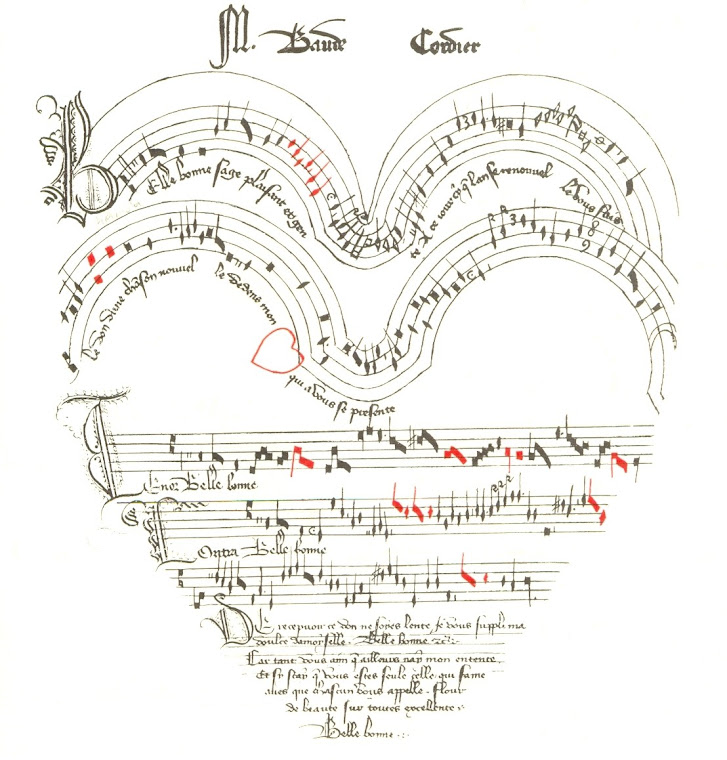

Hume has his own anecdote about the leathern thong and the key in the barrel of wine--an excellent analogy. Let me recount a couple of more from music. I was both an undergraduate and graduate student at McGill University in Montreal and was often impressed with the "delicacy of taste" or what we might call the "precision of perception" of the faculty. I took a graduate seminar in the Shostakovich symphonies and was whistling a theme from one of them as I went into the photocopy room one day. Standing there was a theory professor who immediately said "Shostakovich 5". At the end of that course, by the way, there was a little listening exam where we had to identify not only what symphony a theme came from, but the movement and, if possible, what part of the movement: development, recapitulation? Another time I was taking a course in paleography where you study how music was written before modern notation. Again I was in the photocopy room, this time with a volume from the collected works of Guillaume de Machaut (1300 - 1377). Another theory professor was at the next machine. He glanced over and immediately said, "Machaut". There was nothing on the page to indicate the composer: no text, just the page number. I looked at him with puzzlement and he said, "when I was studying Machaut at Columbia, I spent a lot of time with the collected works and I know the typeface!" This kind of 'delicacy of taste' was not so unusual. A fellow graduate student that I shared an office with was so knowledgeable about Haydn symphonies that he would dash off themes from them on the piano at the drop of a hat. There are one hundred and six Haydn symphonies, by the way.The great resemblance between mental and bodily taste will easily teach us to apply this story. Though it be certain, that beauty and deformity, more than sweet and bitter, are not qualities in objects, but belong entirely to the sentiment, internal or external; it must be allowed, that there are certain qualities in objects, which are fitted by nature to produce those particular feelings. Now as these qualities may be found in a smaller degree, or may be mixed and confounded with each other, it often happens, that the taste is not affected with such minute qualities, or is not able to distinguish all the particular flavours, amidst the disorder, in which they are presented. Where the organs are so fine, as to allow nothing to escape them; and at the same time so exact as to perceive every ingredient in the composition: This we call delicacy of taste, whether we employ these terms in the literal or metaphorical sense. Here then the general rules of beauty are of use; being drawn from established models, and from the observation of what pleases or displeases, when presented singly and in a high degree: And if the same qualities, in a continued composition and in a small degree, affect not the organs with a sensible delight or uneasiness, we exclude the person from all pretensions to this delicacy. To produce these general rules or avowed patterns of composition is like finding the key with the leathern thong; which justified the verdict of SANCHO's kinsmen, and confounded those pretended judges who had condemned them.

Now here is a paragraph that we may indeed find puzzling because it hardly seems that in our present world we so universally acknowledge a "delicate taste of wit or beauty". But this is one of the rewards of reading someone like Hume, who comes from quite a different situation than our own. If the "uniform consent and experience" of his age was in favor of a "delicate taste", then this is good to know. The narcissism of our age seems to scarcely know that such a thing is even possible, let alone desirable! Apparently the only thing we acknowledge as universal is the unique individuality of every special snowflake that is the individual consumer of music. And every special snowflake is listening to, uh, Rihanna!?!It is acknowledged to be the perfection of every sense or faculty, to perceive with exactness its most minute objects, and allow nothing to escape its notice and observation. The smaller the objects are, which become sensible to the eye, the finer is that organ, and the more elaborate its make and composition. A good palate is not tried by strong flavours; but by a mixture of small ingredients, where we are still sensible of each part, notwithstanding its minuteness and its confusion with the rest. In like manner, a quick and acute perception of beauty and deformity must be the perfection of our mental taste; nor can a man be satisfied with himself while he suspects, that any excellence or blemish in a discourse has passed him unobserved. In this case, the perfection of the man, and the perfection of the sense or feeling, are found to be united. A very delicate palate, on many occasions, may be a great inconvenience both to a man himself and to his friends: But a delicate taste of wit or beauty must always be a desirable quality; because it is the source of all the finest and most innocent enjoyments, of which human nature is susceptible. In this decision the sentiments of all mankind are agreed. Wherever you can ascertain a delicacy of taste, it is sure to meet with approbation; and the best way of ascertaining it is to appeal to those models and principles, which have been established by the uniform consent and experience of nations and ages.

But though there be naturally a wide difference in point of delicacy between one person and another, nothing tends further to increase and improve this talent, than practice in a particular art, and the frequent survey or contemplation of a particular species of beauty. When objects of any kind are first presented to the eye or imagination, the sentiment, which attends them, is obscure and confused; and the mind is, in a great measure, incapable of pronouncing concerning their merits or defects. The taste cannot perceive the several excellences of the performance; much less distinguish the particular character of each excellency, and ascertain its quality and degree. If it pronounce the whole in general to be beautiful or deformed, it is the utmost that can be expected; and even this judgment, a person, so unpracticed, will be apt to deliver with great hesitation and reserve. But allow him to acquire experience in those objects, his feeling becomes more exact and nice: He not only perceives the beauties and defects of each part, but marks the distinguishing species of each quality, and assigns it suitable praise or blame. A clear and distinct sentiment attends him through the whole survey of the objects; and he discerns that very degree and kind of approbation or displeasure, which each part is naturally fitted to produce. The mist dissipates, which seemed formerly to hang over the object: the organ acquires greater perfection in its operations; and can pronounce, without danger of mistake, concerning the merits of every performance. In a word, the same address and dexterity, which practice gives to the execution of any work, is also acquired by the same means in the judging of it.

This could hardly be said any more clearly! I have often thought that a good practice for the premiere of a new work would be to play it twice in the same concert: once at the beginning and once at the end so the experience of the audience could become more "exact and nice" the second time. Possible for short works, if not for longer ones.

So much of the music today seems to be intended to take advantage of the "flurry or hurry of thought" and combined with the most distracting videos it is possible to conceive, it seems almost that we are trying to avoid even the possibility of judgement. This is probably an unintended consequence of the commercialization of music. In pop music you want an instant hit. If it takes a few listenings with "attention and deliberation" then forget it! There is indeed a species of beauty which is "florid and superficial" and that is precisely what a lot of pop music is intended to be. I'm sure that in all places and times in the history of music there have been artists that specialized in dressing up in colorful costumes and leaping and cavorting about on stage to the accompaniment of loud pounding on a drum. But I'm pretty sure that they were never before paid so highly as they are today, nor given so much prestige. Did Louis XIV attend private fundraisers with his court jesters?So advantageous is practice to the discernment of beauty, that, before we can give judgment of any work of importance, it will even be requisite, that that very individual performance be more than once perused by us, and be surveyed in different lights with attention and deliberation. There is a flutter or hurry of thought which attends the first perusal of any piece, and which confounds the genuine sentiment of beauty. The relation of the parts is not discerned: The true characters of style are little distinguished: The several perfections and defects seem wrapped up in a species of confusion, and present themselves indistinctly to the imagination. Not to mention, that there is a species of beauty, which, as it is florid and superficial, pleases at first; but being found incompatible with a just expression either of reason or passion, soon palls upon the taste, and is then rejected with disdain, at least rated at a much lower value.

We are still not at the end of Mr. Hume's little essay, but I think I have kicked around Jay-Z enough for today and perhaps bored you, the reader sufficiently as well. Let's end with a Haydn symphony, just to clear the palate:

No comments:

Post a Comment